Whole Chain Traceability: A Successful Research Funding Strategy

Thursday, January 26, 2012 at 11:02PM

Thursday, January 26, 2012 at 11:02PM The following work product represents a critical part of the first successful strategy for obtaining funding from the USDA relative to "whole chain" traceability. It is the work of this author as weaved into a USDA National Integrated Food Safety Initiative (NIFSI) funding submission of the Whole Chain Traceability Consortium™ led by Oklahoma State University and filed in June 2011. This work highlights the usefulness of Pardalis' U.S. patents and patents pending to "whole chain" traceability. It highlights the efficacy of employing granular information objects in the Cloud for providing consumer accessibility to any agricultural supply chain. In August 2011 notification was received of an award ($543,000 for 3 years) under the USDA NIFSI for a project entitled Advancement of a whole-chain, stakeholder driven traceability system for agricultural commodities: beef cattle pilot demonstration (Funding Opportunity Number: USDA-NIFSI RFA (FY 2011), Award Number: 2011-51110-31044).

With the funding of the NIFSI project, the USDA has funded a food safety project that is distinguishable from the Food Safety Modernization Act projects being funded by the FDA and conducted by the Institute of Food Technologists (IFT). Unlike the IFT/FDA projects, the scope of the funded NIFSI project uniquely encompasses consumer accessibility to supply chain information.

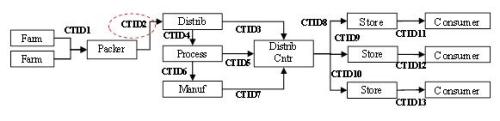

A useful explanation of the benefits of a “whole chain” traceability system may be made with critical traceability identifiers (CTIDs), critical tracking events (CTEs) and Nodes as described in the IFT/FDA Traceability in Food Systems Report. CTEs are those events that must be recorded in order to allow for effective traceability of products in the supply chain. A Node refers to a point in the supply chain when an item is produced, process, shipped or sold. CTEs may be loosely defined as a transaction. Every transaction involves a process that may be separated into a beginning, middle and end.

While important and relevant data exists in any of the phases of a CTE transaction, the entire transaction may be uniquely identified and referenced by a code referred to as a critical tracking identifier (CTID). For example, with the emergence of biosensor development for the real-time detection of foodborne contamination, one may also envision adding associated real-time environmental sampling data from each node.

What is not described or envisioned in the IFT/FDA Traceability in Food Systems Report is the challenge of using even top of the line “one up/one down” product traceability systems that, notwithstanding the use of a single CTID, are inherently limiting in the data sharing options provided to both stakeholders and government regulators. Pause for a moment and compare the foregoing drawing with the next drawing. Compare CTID2 in both drawings with CTID2A, CTID2B, etc. in the next drawing. The IFT/FDA food safety projects described above are at best implementing top of the line "one up/one down" product traceability systems with the use of a single CTID. But with “whole chain” product traceability, in which CTID2 is essentially assigned down to the datum level, transactional and environmental sampling data may in real-time be granularly placed into the hands of supply chain partners, food safety regulators, or even retail customers.

The scope of “whole chain” chain information sharing within the funded USDA NIFSI project goes well beyond the “one up/one down” information sharing of the IFT/FDA projects. The NIFSI project addresses a new way of looking at information sharing for connecting supply chains with consumers. This is essentially accomplished with a system in which a content provider creates data which is then fixed (i.e., made immutable) and users can access that immutable data but cannot change it.

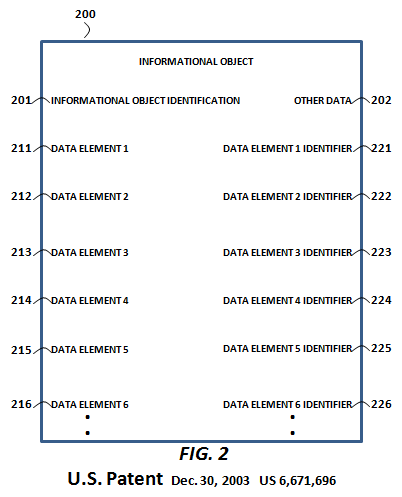

The granularity of Pardalis' Common Point Authoring (CPA) system (as is necessary for a “whole chain” product traceability system) is characterized by the following patent drawing of an informational object (e.g., a document, report or XML object) whose immutable data elements are radically and uniquely identified. The similarities between the foregoing object containing CTID2A, CTID2B, etc., and the immutable data element identifiers of the following drawing, should be self-evident.

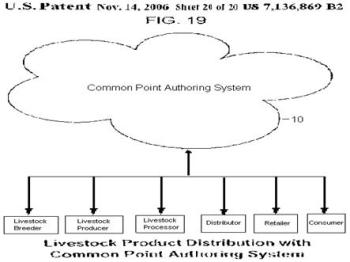

For the purposes of the NIFSI funding opportunity, the Pardalis CPA system invention was appropriately characterized as a “whole chain” product traceability system. A further, high-altitude drawing, characterized the application of the invention to a major U.S. agricultural supply chain:

Several questions were required in the USDA's NIFSI "Review Package" to be addressed before actual funding. The responses to two of those questions were crafted by this author. They are worth inserting here ....

Question 1: A reviewer was skeptical that the system would be capable of handling different levels of data (consumer, producer, RFID, bar code) seamlessly.

There is an assumption in the reviewer’s opinion that data is different because it is consumer, producer, RFID, bar code, etc. The proposed pilot project is based on a premise that data is data. The difference in data that is perceived by the reviewer is not in its categorization per se but in its proprietary nature. That is, it is perceived to be different because it is locked up (often in categories of consumer, producer, RFID, bar code, etc.) in proprietary data silos along the supply and demand chains. It is reasonable to have this viewpoint given the prevalence of "one-up/one-down" data sharing in supply chains. As stated in the Positive Aspects of the Proposal, “[t]he use of open source software and the ability to add consumer access to the tracability (sic) system set this proposal apart from other similar proposals.” The proposed pilot project will demonstrate how an open source approach to increasing interoperability between enterprise data silos (buttressed by metadata permissions and security controls in the hands of the actual data producers) will provide new "whole chain" ways of looking at information sharing in enterprise supply and consumer demand chains. For instance, consumers could opt for retailers to automatically populate their accounts from their actual point-of-sale retail purchases. Consumers could additionally populate accounts in a multi-tenancy social network (like Facebook) using smartphone bar code image capturing applications. Supplemented by cross-reference to an industry GTIN/GLN database, the product identifiers would be associated with company names, time stamps, location and similar metadata. This could empower consumers with a one-stop shop for confidentially reporting suspicious food to FoodSafety.gov. Likewise, consumers could be provided with real-time, relevant food recall information in their multi-tenancy, social networking accounts, and their connected smartphone applications.

Question 2: A member of the panel was skeptical that the consumer accessibility would be largely attractive as this capability currently has limited appeal among consumers.

We recognize this viewpoint to be a highly prevalent opinion within an ag and food industry predominantly sharing data in a “one-up/one-down” manner. When one uses a smartphone today to scan an item in a grocery store, the probability of being able to retrieve any data from the typical ag and food supply chain is very low. However, we have been highly influenced in our thinking by the existing data showing that many consumers do not take appropriate protective actions during a foodborne illness outbreak or food recall. Furthermore, 41 percent of U.S. consumers say they have never looked for any recalled product in their home. Conversely, some consumers overreact to the announcement of a foodborne illness outbreak by not purchasing safe foods. We have been further influenced by how producers of organic and natural products are adopting rapidly evolving smartphone and mobile technologies as a way of communicating directly with consumers, and increasing their market share. We contend that by increasing supply chain transparency with real-time, whole chain technologies, “consumer accessibility” will become more and more appealing. We contend this to be especially true when there is a product recall and the products are already in the home. And so, again, our high interest in working with FoodSafety.gov.

The foregoing strategy and comments may be freely cited with attribution to this author as CEO of Pardalis, Inc. It is offered in the spirit of the "sharing is winning" principles of the Whole Chain Traceability Consortium™ (now being rebranded as @WholeChainTrace™). However, no right to use Pardalis' patent or patents pending is conveyed thereby. If you wish to be a research collaborator with Pardalis, or to license or use Pardalis' patented innovations, please contact the author.

Steve Holcombe

Steve Holcombe

All indications are that the emerging Wikidata Project, the next iteration of Wikipedia, will authorize end-users to centrally register immutable data elements (e.g., someone's birth date). It is no surprise that the primary benefactors of the Wikidata Project include Paul Allen's Institute for Artificial Intelligence and Google because from these immutable data elements will be created trustworthy informational objects for supporting varying semantic relationships (i.e., ontologies).

"The overall project will have three phases, the first of which involves creating one Wikidata page for each Wikipedia entry across Wikipedia’s over 280 supported languages. This will provide the online encyclopedia with one common source of structured data that can be used in all articles, no matter which language they’re in. For example, the date of someone’s birth would be recorded and maintained in one place: Wikidata. Phase one will also involve centralizing the links between the different language versions of Wikipedia. This part of the work will be finished by August 2012."

See http://techcrunch.com/2012/03/30/wikipedias-next-big-thing-wikidata-a-machine-readable-user-editable-database-funded-by-google-paul-allen-and-others/

I will be speaking about the Wikidata Project in my keynote presentation "Data objects and information exchange for whole chain traceability" at the Smart AgriMatics Conference in Paris in mid-June, 2012. For more information see http://www.smartagrimatics.eu/ConferenceInformation/Program.aspx#PlenaryOpeningSession.

Steve Holcombe

Steve Holcombe

ADVANCEMENT OF A WHOLE-CHAIN, STAKEHOLDER DRIVEN TRACEABILITY SYSTEM FOR AGRICULTURAL COMMODITIES: BEEF CATTLE PILOT DEMONSTRATION

Sponsoring Institution: USDA NIFA

Grant No. 2011-51110-31044

Project Timeline: Sep 1, 2011 to Aug 31, 2014

Recipient Organization: OKLAHOMA STATE UNIVERSITY, BIOSYSTEMS & AG ENGINEERING, STILLWATER,OK 74078

Project Director: Buser, Michael | 405-744-5288 | buser@okstate.edu

Project Methods: The software development for a working, scalable stakeholder-driven "whole chain" agricultural commodity traceability system is broken down into four categories: 1) system architecture, 2) system software, 3) content-centric networking and 4) stakeholder feedback.

System Architecture: We propose to implement the distributed system using a content-centric networking (CCN) data framework such as the CCNx framework currently under development by Xerox PARC, (sic)

System Software: The proposed WCTS system will extend the existing supply chain software of Pardalis, Inc. As multiple stakeholders may be generating and accessing shared data, we will develop algorithms for data synchronization, reconciliation and certification. The system must provide reports such as supply chain traceability reports. A browser-based version of the user interface will be designed and implemented. A critical subset of these will be implemented as applications in mobile Android based smart phones.

Content-Centric Networking for Food Traceability: Initially, CCNx will be applied for commodity traceability to determine system performance characteristics such as bandwidth, caching requirements, delays, throughput, etc. CCNx's performance will be compared to the Internet Protocol. The security of CCNx for commodity traceability will be analyzed. In the second phase we will seek to alleviate the bottlenecks and weaknesses identified in the first phase, particularly the security vulnerabilities and trust implementation in the whole chain. We will first identify the security goals for a whole chain commodity traceability system to define security policies. These policies, which will include access rights, for example, will be enforced by credentials. Second, we will analyze the different levels of protection and privacy required by the different types of content. Third, we will implement trust in the whole supply chain within the CCNx framework by integrating credentials (Blaze et. al. 1996) with reputation-based trust management (Zacharia 2000) and policy-based trust management. We propose to create and discover by content the distributed credentials, reputations, users and data and thereby create a trust chain that is content-centric. Sanitation algorithms (Dilys 2007)) to filter content will be explored with a view to incorporating them within CCNx to ensure privacy.

The above information was found at the following link on 4 September 2012: http://www.reeis.usda.gov/web/crisprojectpages/0226992-advancement-of-a-whole-chain-stakeholder-driven-traceability-system-for-agricultural-commodities-beef-cattle-pilot-demonstration.html. However since that time the foregoing information has been substituted with other language including the following:

Non Technical Summary: Traceability is a key component in developing a safe food supply, as evidenced by the recent outbreak of foodborne illnesses attributed to spinach, peppers, and tomatoes in the United States and the ongoing e-coli outbreak in Europe with 27 deaths reported to date. The European Union has agreed to pay over $300 million to farmers who suffered losses. The Centers for Disease Control reported that salmonella infection rates are increasing with one million people sickened by food-borne pathogens each year. Unfortunately, the current approach to product traceability is one-up, one-back information sharing at the GTIN (global trade item number) lot level. This type of traceability system has many disadvantages, including lack of privacy, and fails to maximize system benefits such as efficiency and more complete or "whole-chain" information sharing. This approach is fraught with inherent delays, limiting consumers' and regulators' ability to identify the contaminant source and limiting mitigation efforts in the event of outbreaks or bioterrorism. This lack of critical information can cause significant economic losses to multiple industries resulting from public uncertainty on the potential for human hazard, affecting even those not connected with outbreaks. Conversely, research suggests that whole-chain traceability can substantially limit the economic loss of food safety events.